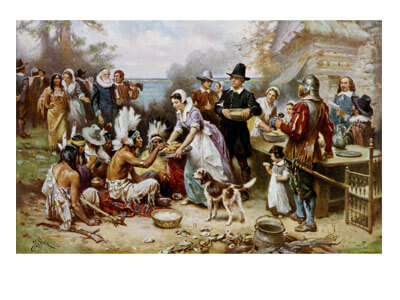

In the fall of 1621, 90 Wampanoag Indians and 52 English colonists gathered for a three-day harvest feast. How did Americans get from that celebration to the Thanksgiving ‘traditions’ we observe today?

PLYMOUTH, MASS.

Everyone knows about the Pilgrims and the Indians, right? How the two groups gathered peacefully in Plymouth, Mass., to feast on juicy turkeys and colorful pumpkin pies.

The trouble is, almost everything we’ve been taught about the first Thanksgiving in 1621 is a myth. The holiday has two distinct histories – the actual one and a romanticized portrayal.

Today, Americans celebrate a holiday based largely on the latter, whose details of turkey and cranberry sauce decorating one long table stem from the creative musings of a magazine editor in the mid-1800s.

The true history has been a difficult one to uncover. Staff at Plimoth Plantation, which occupies several acres on the outskirts of the city of Plymouth, just north of Cape Cod, have been in the vanguard of researching the event. But a big obstacle remains: Everything historians know today is based on two passages written by colonists.

Participants’ accounts

In a letter to a friend, dated December 1621, Edward Winslow wrote: “Our harvest being gotten in, our Governor sent four men on fowling, that so we might after a more special manner rejoice together, after we had gathered the fruit of our labors; they four in one day killed as much fowl as, with a little help beside, served the Company almost a week, at which time, among other Recreations, we exercised our Arms, many of the Indians coming amongst us, and among the rest their greatest King Massasoit, with some 90 men, whom for three days we entertained and feasted and they went out and killed five Deer, which they brought to the Plantation and bestowed on our Governor, and upon the Captain and others.”

Twenty years later, William Bradford wrote a book that provides a few more hints as to what might have been on that first Thanksgiving table. But his book was stolen by British looters during the Revolutionary War and therefore didn’t have much influence on how Thanksgiving was celebrated until it turned up many years later.

No one is certain whether the Wampanoag and the colonists regularly sat together and shared their food, or if the three-day “thanksgiving” feast Mr. Winslow recorded for posterity was a one-time event.

In the culture of the Wampanoag Indians, who inhabited the area around Cape Cod, “thanksgiving” was an everyday activity.

“We as native people [traditionally] have thanksgivings as a daily, ongoing thing,” says Linda Coombs, associate director of the Wampanoag program at Plimoth Plantation. “Every time anybody went hunting or fishing or picked a plant, they would offer a prayer or acknowledgment.”

But for the 52 colonists – who had experienced a year of disease, hunger, and diminishing hopes – their bountiful harvest was cause for a special celebration to give thanks.

“Neither the English people nor the native people in 1621 knew they were having the first Thanksgiving,” Ms. Coombs says. No one knew that the details would interest coming generations.

“We’re not sure why Massasoit and the 90 men ended up coming to Plimoth,” Coombs says. “There’s an assumption that they were invited, but nowhere in the passage does it say they were. And the idea that they sat down and lived happily ever after is, well, untrue. The relationship between the English and the Wampanoag was very complex.”

Since they did not speak the same language, the extent to which the colonists and Indians intermingled remains a mystery. But a few details of that first Thanksgiving are certain, says Kathleen Curtin, food historian at the Plimoth Plantation.

What was on the menu?

First, wild turkey was never mentioned in Winslow’s account. It is probable that the large amounts of “fowl” brought back by four hunters were seasonal waterfowl such as duck or geese.

And if cranberries were served, they would have been used for their tartness or color, not the sweet sauce or relish so common today. In fact, it would be 50 more years before berries were boiled with sugar and used as an accompaniment to meat.

Potatoes weren’t part of the feast, either. Neither the sweet potato nor the white potato was yet available to colonists.

The presence of pumpkin pie appears to be a myth, too. The group may have eaten pumpkins and other squashes native to New England, but it is unlikely that they had the ingredients for pie crust – butter and wheat flour. Even if they had possessed butter and flour, the colonists hadn’t yet built an oven for baking.

While we have been able to work out which modern dishes were not available in 1621, just what was served is a tougher nut to crack.

A couple of guesses can be made from other passages in Winslow’s correspondence about the general diet at the time: lobsters, mussels, “sallet herbs,” white and red grapes, black and red plums, and flint corn.

“We have only one documented harvest feast that occurred between the cultures,” Curtin points out. “You don’t hear about [any other] harvests occurring between them. I assume that they did on some level, but it’s fascinating that it is just that one source, one sentence in one letter. I wonder what else is there that someone just didn’t jot down, and we now know nothing about.”

Until the early 1800s, Thanksgiving was considered to be a regional holiday celebrated solemnly through fasting and quiet reflection.

But the 19th century had its own Martha Stewart, and it didn’t take her long to turn New England fasting into national feasting. Sarah Josepha Hale, editor of the popular Godey’s Lady’s Book, stumbled upon Winslow’s passage and refused to let the historic day fade from the minds – or tables – of Americans. This established trendsetter filled her magazine with recipes and editorials about Thanksgiving.

It was also about this time – in 1854, to be exact – that Bradford’s history book of Plymouth Plantation resurfaced. The book increased interest in the Pilgrims, and Mrs. Hale and others latched onto the fact he mentioned that the colonists had killed wild turkeys during the autumn.

In her magazine Hale wrote appealing articles about roasted turkeys, savory stuffing, and pumpkin pies – all the foods that today’s holiday meals are likely to contain.

In the process, she created holiday “traditions” that share few similarities with the original feast in 1621.

In 1858, Hale petitioned the president of the United States to declare Thanksgiving a national holiday. She wrote: “Let this day, from this time forth, as long as our Banner of Stars floats on the breeze, be the grand Thanksgiving holiday of our nation, when the noise and tumult of worldliness may be exchanged for the length of the laugh of happy children, the glad greetings of family reunion, and the humble gratitude of the Christian heart.”

Five years later, Abraham Lincoln declared the last Thursday of November “as a day of Thanksgiving and Praise to our beneficent Father who dwelleth in the Heavens.”